Double Entry System

The field of accounting—both the older manual systems and today's basic accounting software—is based on the 500-year-old accounting procedure known as double entry. Double entry is a simple yet powerful concept: each and every one of a company's transactions will result in an amount recorded into at least two of the accounts in the accounting system.

The Chart of Accounts

To begin the process of setting up Joe's accounting system, he will need to make a detailed listing of all the names of the accounts that Direct Delivery, Inc. might find useful for reporting transactions. This detailed listing is referred to as a chart of accounts. (Accounting software often provides sample charts of accounts for various types of businesses.)

As he enters his transactions, Joe will find that the chart of accounts will help him select the two (or more) accounts that are involved. Once Joe's business begins, he may find that he needs to add more account names to the chart of accounts, or delete account names that are never used. Joe can tailor his chart of accounts so that it best sorts and reports the transactions of his business.

Because of the double entry system all of Direct Delivery's transactions will involve a combination of two or more accounts from the balance sheet and/or the income statement. Marilyn lists out some sample accounts that Joe will probably need to include on his chart of accounts:

Note: To learn more about the chart of accounts, visit: Explanation of Chart of AccountsQuiz for Chart of Accounts

Balance Sheet accounts:

- Asset accounts (Examples: Cash, Accounts Receivable, Supplies, Equipment)

- Liability accounts (Examples: Notes Payable, Accounts Payable, Wages Payable)

- Stockholders' Equity accounts (Examples: Common Stock, Retained Earnings)

Income Statement accounts:

- Revenue accounts (Examples: Service Revenues, Investment Revenues)

- Expense accounts (Examples: Wages Expense, Rent Expense, Depreciation Expense)

To help Joe really understand how this works, Marilyn illustrates the double entry with some sample transactions that Joe will likely encounter.

Sample Transaction #1

On December 1, 2014 Joe starts his business Direct Delivery, Inc. The first transaction that Joe will record for his company is his personal investment of $20,000 in exchange for 5,000 shares of Direct Delivery's common stock. Direct Delivery's accounting system will show an increase in its account Cash from zero to $20,000, and an increase in its stockholders' equity account Common Stock by $20,000. Both of these accounts are balance sheet accounts. There are no revenues because no delivery fees were earned by the company, and there were no expenses.

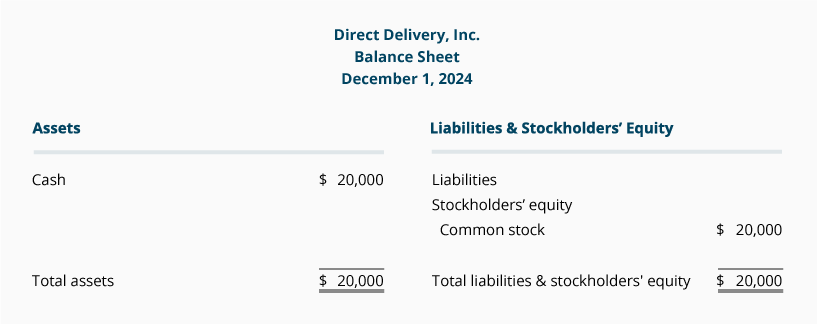

After Joe enters this transaction, Direct Delivery's balance sheet will look like this:

Marilyn asks Joe if he can see that the balance sheet is just that-in balance. Joe looks at the total of $20,000 on the asset side, and looks at the $20,000 on the right side, and says yes, of course, he can see that it is indeed in balance.

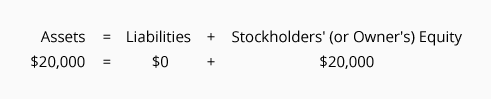

Marilyn shows Joe something called the basic accounting equation, which, she explains, is really the same concept as the balance sheet, it's just presented in an equation format:

The accounting equation (and the balance sheet) should always be in balance.

Debits and Credits

Did the first sample transaction follow the double entry system and affect two or more accounts? Joe looks at the balance sheet again and answers yes, both Cash and Common Stock were affected by the transaction.

Marilyn introduces the next basic accounting concept: the double entry system requires that the same dollar amount of the transaction must be entered on both the left side of one account, and on the right side of another account. Instead of the word left, accountants use the word debit; and instead of the word right, accountants use the word credit. (The terms debit and credit are derived from Latin terms used 500 years ago.)

Here's a Tip

Debit means left.

Credit means right.

Joe asks Marilyn how he will know which accounts he should debit—meaning he should enter the numbers on the left side of one account—and which accounts he should credit—meaning he should enter the numbers on the right side of another account. Marilyn points back to the basic accounting equation and tells Joe that if he memorizes this simple equation, it will be easier to understand the debits and credits.

Here's a Tip

Memorizing the simple accounting equation will help you learn the debit and credit rules for entering amounts into the accounting records.

Let's take a look at the accounting equation again:

Just as assets are on the left side (or debit side) of the accounting equation, the asset accounts in the general ledger have their balances on the left side. To increase an asset account's balance, you put more on the left side of the asset account. In accounting jargon, you debit the asset account. To decrease an asset account balance you credit the account, that is, you enter the amount on the right side.

Just as liabilities and stockholders' equity are on the right side (or credit side) of the accounting equation, the liability and equity accounts in the general ledger have their balances on the right side. To increase the balance in a liability or stockholders' equity account, you put more on the right side of the account. In accounting jargon, you credit the liability or the equity account. To decrease a liability or equity, you debit the account, that is, you enter the amount on the left side of the account.

As with all rules, there are exceptions, but Marilyn's reference to the accounting equation may help you to learn whether an account should be debited or credited.

Since many transactions involve cash, Marilyn suggests that Joe memorize how the Cash account is affected when a transaction involves cash: if Direct Delivery receives cash, the Cash account is debited; when Direct Delivery pays cash, the Cash account is credited.

Here's a Tip

When a company receives cash, the Cash account is debited.

When the company pays cash, the Cash account is credited.

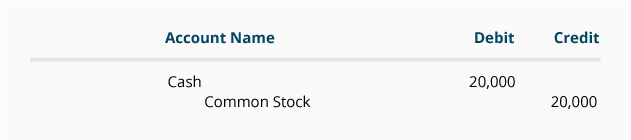

Marilyn refers to the example of December 1. Since Direct Delivery received $20,000 in cash from Joe in exchange for 5,000 shares of common stock, one of the accounts for this transaction is Cash. Since cash wasreceived, the Cash account will be debited.

In keeping with double entry, two (or more) accounts need to be involved. Because the first account (Cash) wasdebited, the second account needs to be credited. All Joe needs to do is find the right account to credit. In this case, the second account is Common Stock. Common stock is part of stockholders' equity, which is on the right side of the accounting equation. As a result, it should have a credit balance, and to increase its balance the account needs to be credited.

Accountants indicate accounts and amounts using the following format:

Accountants usually first show the account and amount to be debited. On the next line, the account to be credited is indented and the amount appears further to the right than the debit amount shown in the line above. This entry format is referred to as a general journal entry.

(With the decrease in the price of computers and accounting software, it is rare to find a small business still using a manual system and making entries by hand. Accounting software has made the process of recording transactions so much easier that the general journal is rarely needed. In fact, entries are often generated automatically when a check or sales invoice is prepared.)

No comments:

Post a Comment